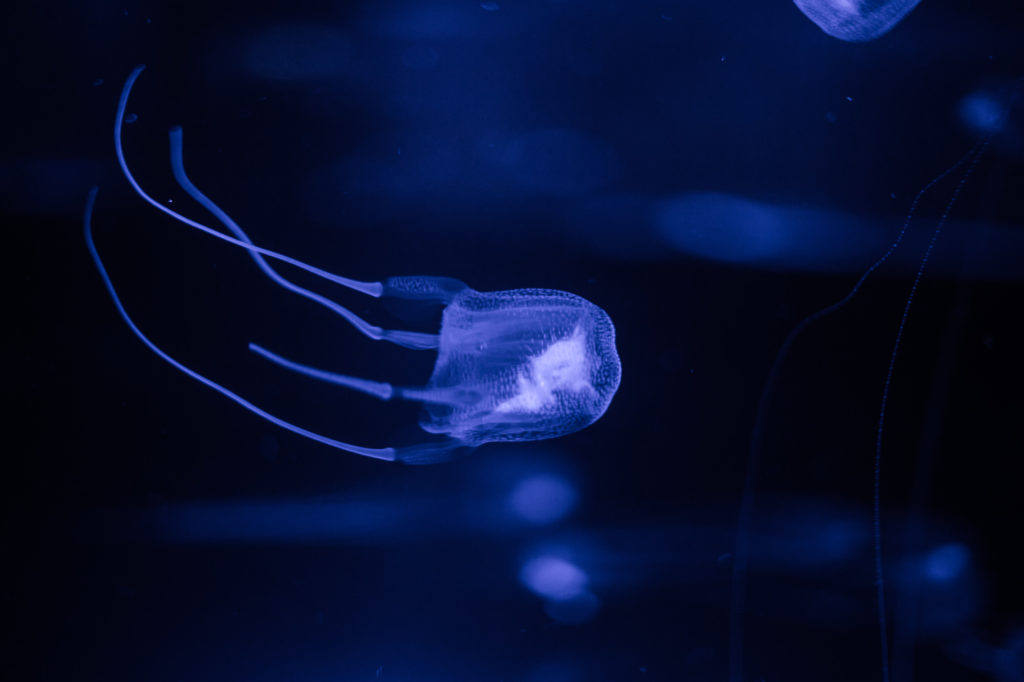

Not many sea creatures inspire such fear—and wonder—as jellyfish. They strike dread in the heart of swimmers and snorkelers, and yet serve their own vital role in the marine ecosystem. All things considered, most “sea jellies” don’t pose the panic-mode threat popular media makes them out to be. That said, it’s definitely true that some species can deliver a painful—even seriously dangerous—sting, so it’s good to know the basics of these fascinating, ghostly undersea drifters.

Table of Contents

- An Intro to Jellyfish

- Jellyfish Stats

- When is Jellyfish Season

- Jellyfish Species in Each State

- Jellyfish Safety Tips: Avoiding/Preventing Stings

- What to Do If You’re Stung by a Jellyfish

- Top 5 Jellyfish Myths

- Top 10 FAQ about Jellyfish

- Other Things That Suck

- Underwater Coloring Sheet

- Jellyfish Videos

- Jellyfish Sting Stories

An Intro to Jellyfish

What exactly are jellyfish, anyhow? Well, they’re animals—the simplest swimming animals of all, in fact—known as cnidarians. They’re definitely not fish: They’re invertebrates, lacking a backbone.

“True jellyfish” belong to a class of cnidarians called Scyphozoa. Box jellyfish fall within the class Cubozoa. We’ll mainly be focusing on those two groups of cnidarians, but it’s important to note many cnidarians in the class Hydrozoa are also loosely called “jellyfish,” including freshwater jellyfish, clinging jellyfish, by-the-wind sailors, and the notorious Portuguese man-o’-war.

We’ll talk more about the Man-O’War a bit later in this write-up, even though it’s not technically a jellyfish; it’s actually a siphonophore, a colony of organisms living together as one. Also, the well-known “comb jellies” aren’t true jellyfish, as they aren’t cnidarians.

Sea jellies in their mature, or medusa, form have a roundish or squarish saclike body called a bell to which tentacles are attached. As the National Science Foundation notes, water composes about 95 percent of a jellyfish’s mass. Their rudimentary design helps explain their enormous evolutionary success: Jellies have been around for more than 500 million years! They’re found in all marine environments, from shallow coastal waters to the ocean deeps, and from polar to tropical seas.

Jellyfish tentacles include stinging cells—the part we all pay attention to, of course. (Some jellies also sport stinging cells in their bells.) The stinging cells contain structures called nematocysts that inject venom on contact at lightning speed. All true jellies can sting, but the stings of many species are harmless—and often painless—to people.

Mainly carnivorous, jellyfish use their stinging tentacles to kill plankton and other small organisms that stray into them. Not especially strong swimmers, jellyfish mainly use this passive method of capturing prey while drifting with the current or propelling themselves up and down the water column. Their stings also, of course, can be used in defense. (Quite a few sea

creatures prey on jellyfish, including the biggest of all sea turtles: the mighty leatherback.)

Jellyfish develop from larva that turn into polyps, which typically fix themselves to the ocean floor or floating objects as stationary forms. The polyp stage may last for years until conditions become favorable for the next phase of growth. That next phase involves the polyps “budding” off tiny jellyfish that soon grow into full-size medusas.

Of the several hundred species of true jellyfish, only a relatively few pose a serious threat to people. The most dangerous are generally considered the cubozoans or box jellyfish, named for their box-shaped bells; these include perhaps 20 or 30 species of tropical and subtropical jellies. Box jellyfish are most notorious in Indo-Pacific and Australian waters, where some species,

such as the sea wasp, are downright deadly.

Some species of box jellyfish are found in U.S. waters, including Hawaii and Florida. But many of the familiar coastal jellyfish in this country, such as moon jellies and sea nettles, belong to the scyphozoans, some of which can deliver painful (though not usually fatal) stings.

While most jellyfish are on the small, even minuscule, side of things, some can reach impressive sizes. The biggest is the lion’s mane jellyfish, a widespread species of temperate and Arctic waters (including off both coasts of the Lower 48). A lion’s mane jellyfish’s bell may be more than six feet across, and its tentacles can stretch more than 100 feet!

Jellyfish Stats

It’s estimated that perhaps 150 million people are stung by jellyfish around the world every year. A couple of hundred thousand stings are commonly reported in Florida annually.

The number of people who die from jellyfish stings isn’t exactly known; experts reckon fatal box-jellyfish stings are probably significantly under-reported. The actual figure may be in the hundreds or even thousands. As many as 150 people in the Philippines may die from box jellyfish every year.

But deaths from jellyfish are pretty rare in the U.S., where most “problematic” species, such as the sea nettle, deliver painful but not truly potent stings. Most jellyfish stings in this country don’t require anything more than basic first-aid treatment. More serious cases involving hospitalization tend to be issues of allergic reaction.

When is Jellyfish Season?

There can definitely be seasonal concentrations of certain kinds of jellyfish in certain waters. In the Chesapeake Bay, for instance, lion’s mane and cannonball jellyfish are more often seen in winter, while sea nettles and moon jellies are more common in summer. The Puget Sound often sees large summertime gatherings (or “smacks”) of moon jellies.

In subtropical waters, box jellies are more of a summer phenomenon in both the Northern and Southern hemispheres, though deeper in the tropics stings are reported year-round. In Hawaii, box jellyfish often show up in coastal waters about a week and a half after the full moon. This has to do with lunar-timed breeding.

More generally, certain weather and surf patterns may mean being especially jellyfish-aware. For example, inshore currents and strong onshore winds can drive jellies into beachfront shallows or bays.

Sometimes, for reasons not entirely clear, certain coasts may experience exceptional swarms of jellyfish. Scientists have noted that these jellyfish “blooms” are increasing, though the exact cause isn’t clear; overfishing because it’s reduced populations of fish and other predators and competitors of jellyfish may be partly to blame.

Generally speaking, many seacoasts have jellyfish of one kind or another along them any time of year. In the U.S. and many other places, jellyfish stings are more common in the summer, but that’s mainly simply because more people are in the water then.

Jellyfish Species in Each State

Rather than list literally all the jellyfish native to each U.S. state, we’ll highlight some of the most common cnidarians as well as those that pose a threat to people.

Sea and bay nettles (two closely related species only recently distinguished as separate) likely cause the most stings along the U.S. Atlantic and Gulf coasts. Lion’s mane jellyfish are another species to watch out for along the Atlantic seaboard, given their potentially painful sting; sea wasps or box jellies are dangerous in Southeastern waters, though they aren’t the most notorious Indo-Pacific/Australian species. Box jellies are also prevalent in the Hawaiian Islands.

Maine

-Lion’s Mane

-White Cross Jelly

-Moon Jelly

New Hampshire

-Lion’s Mane

-White Cross Jelly

-Moon Jelly

Massachusetts

-Lion’s Mane

-White Cross Jelly

-Moon Jelly

-Sea Nettle

-Bay Nettle

-Cannonball Jelly

-Mushroom Jelly

New York

-Lion’s Mane

-White Cross Jelly

-Moon Jelly

-Sea Nettle

-Bay Nettle

-Cannonball Jelly

-Mushroom Jelly

New Jersey

-Lion’s Mane

-White Cross Jelly

-Moon Jelly-Sea Nettle

-Bay Nettle

-Cannonball Jelly

-Mushroom Jelly

Delaware

-Lion’s Mane

-White Cross Jelly

-Moon Jelly

-Sea Nettle

-Bay Nettle

-Cannonball Jelly

-Mushroom Jelly

Maryland

-Lion’s Mane

-White Cross Jelly

-Moon Jelly

-Sea Nettle

-Bay Nettle

-Cannonball Jelly

-Mushroom Jelly

Virginia

-Lion’s Mane

-White Cross Jelly

-Moon Jelly

-Sea Nettle

-Bay Nettle

-Cannonball Jelly

-Mushroom Jelly

North Carolina

-Sea Wasp

-Lion’s Mane

-White Cross Jelly

-Moon Jelly

-Sea Nettle

-Bay Nettle

-Cannonball Jelly

-Mushroom Jelly

South Carolina

-Sea Wasp

-Lion’s Mane

-White Cross Jelly

-Moon Jelly

-Sea Nettle

-Bay Nettle

-Cannonball Jelly

-Mushroom Jelly

Georgia

-Sea Wasp

-Lion’s Mane

-White Cross Jelly

-Moon Jelly

-Sea Nettle

-Bay Nettle

-Cannonball Jelly

-Mushroom Jelly

Florida

-Sea Wasp

-Upside-down Jellyfish

-Pink Meanie

-Mauve Stinger

-Lion’s Mane

-White Cross Jelly

-Moon Jelly

-Sea Nettle

-Bay Nettle

-Cannonball Jelly

-Mushroom Jelly

-Australian Spotted Jellyfish

Alabama

-Bay Nettle

-Moon Jelly

-Cannonball Jelly

-Sea Wasp

-Pink Meanie

-Mushroom Jelly

-Lion’s Mane

-Australian Spotted Jelly

-Mauve Stinger

Mississippi

-Bay Nettle

-Moon Jelly

-Cannonball Jelly

-Sea Wasp

-Pink Meanie

-Mushroom Jelly

-Lion’s Mane

-Australian Spotted Jelly

-Mauve Stinger

Louisiana

-Bay Nettle

-Moon Jelly

-Cannonball Jelly

-Sea Wasp

-Pink Meanie

-Mushroom Jelly

-Lion’s Mane

-Australian Spotted Jelly

-Mauve Stinger

Texas

-Bay Nettle

-Moon Jelly

-Cannonball Jelly

-Sea Wasp

-Pink Meanie

-Mushroom Jelly

-Lion’s Mane

-Australian Spotted Jelly

-Mauve Stinger

California

-Pacific Sea Nettle

-Black Sea Nettle

-Moon Jelly

-Lion’s Mane

-Water Jelly

-Fried Egg Jelly

Oregon

-Pacific Sea Nettle

-Lion’s Mane

-Moon Jelly

-Water Jelly (Craspedacusta Sowerbii)

-Fried Egg Jelly

Washington

-Pacific Sea Nettle

-Lion’s Mane

-Moon Jelly

-Water Jelly

-Fried Egg Jelly

Alaska

-Moon Jelly

-Pacific Sea Nettle

-Lion’s Mane

-Fried Egg Jelly

Hawaii

-Box Jellies (multiple species)

-Moon Jelly

-Spotted Jelly

-Upside-down Jelly

International Jellyfish:

Now that we’ve got the U.S. covered, what is there to learn about jellyfish from a global perspective?

Asia

Asia is known to frequently eat jellyfish like the Flame Jellyfish and the Sand Jellyfish. There are also Barrel Jellies (also known as Rhizostome Jellyfishes) in abundance.

Africa

The Purple Compass Jelly is a common species of jellyfish along the continent of Africa, but there are other species like the South African box jellyfish and barrel jellyfish that are also quite common in the area.

South America

South American Sea Nettle is one species that is found often in South America — hence the name. Also known as the Chrysaora Plocamia, this species has been recorded along the coast of Peru, Chile, Argentina, and Uruguay.

Antarctica

There are some cold waters surrounding Antarctica, but that doesn’t mean that it’s impossible for jellyfish to live in the area. In fact, sea ice remains thick enough for protection while the metabolism of jellyfish slows down — slowing down the need for food. The jellyfish most found in this area is the Diplulmaris Antarctica jellyfish species.

Europe

In Europe, the most common types of jellyfish are the Moon Jellyfish, the Upside-Down Jellyfish, The Barrel Jellyfish, and the Blue Jellyfish — all of these are relatively harmless.

Australia

In Australia, you’ll find some lethal jellyfish like the Australian box jellyfish and the Irukandji jellyfish. Another popular jellyfish is the Purple Stinger, also known as the Purple People Eater, which generally are more annoying than harmful. Other than these top 3, you’ll find; the Australian spotted jellyfish, other species of the box jellyfish, and the Jelly Blubber.

Jellyfish Safety Tips: Avoiding/Preventing Stings:

Most of the time, it’s fairly easy to avoid being stung by a jellyfish. Being especially cautious or staying out of the water altogether during peak jellyfish season in areas that experience that kind of thing is one obvious preventative measure. So is abiding by posted beach warnings and paying attention to any lifeguard advisories.

Any time of year, stay watchful while swimming or snorkeling so you can steer clear of any drifting jellies. Be especially on alert where you see a lot of floating material (flotsam) massed together, as along windward beaches or the borders of currents. Jellyfish may also be driven into the same spots where wind and currents accumulate flotsam.

It goes without saying that you should think twice before swimming off a beach that’s piled with washed-up jellyfish. And avoid touching such beached jellies: Some may still be alive, for one thing, and even those that have been dead for weeks can still result in a sting if handled. Just because it looks dried-up doesn’t mean you should prod it with a finger or heel.

Wearing protective clothing such as wetsuits while in the water can reduce the likelihood of a sting. People swimming within the range of dangerous box jellyfish often wear “stinger suits”—thicker, full-body variations on the wetsuit specifically designed to protect from jellies—as well as gloves and booties. There’s a jellyfish-repellent lotion available for exposed skin (Safe Sea); petroleum jelly is sometimes recommended as well.

It’s worth emphasizing a basic piece of ocean safety advice: Never swim alone! While most jellyfish stings are not in and of themselves deadly, stung individuals may experience panic, pain, nausea, or other adverse effects that may put them at risk of drowning. Also, those who suffer an allergic reaction can be in serious trouble if nobody else is around to help.

What to Do If You’re Stung by a Jellyfish

Despite your best efforts, you or somebody in your party may end up stung by a jellyfish while taking a dip. The most “see-through” kinds of jellies can be difficult to spot, for one thing. And sometimes loose tentacles or tentacle bits from a torn-up or dashed-apart jellyfish being washed about in the waves may sting you.

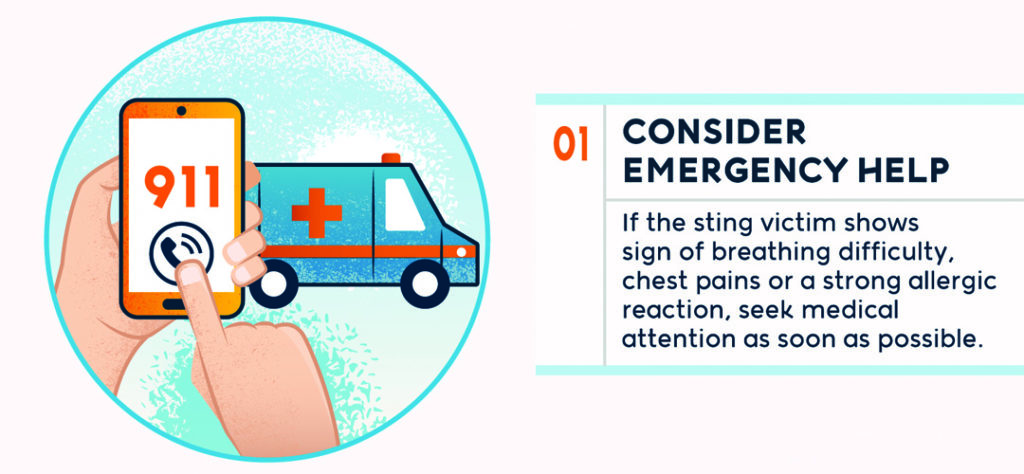

Consider Emergency Help

If the sting victim shows signs of breathing difficulty, chest pains, or a strong allergic reaction, it’s important to seek medical attention as soon as possible. That’s also a good idea if the person was stung numerous times or across a large area of the body. Call 911 or the toll-free national Poison Help Hotline at 1-800-222-1222, which can connect you with the local poison-

control clinic.

Use Oral Anti-Histamine

Use an oral antihistamine or injection of epinephrine if the sting victim is having an allergic reaction.

Remove Jellyfish Tentacles

To treat a jellyfish sting in general, remove any remaining tentacles on the skin using tweezers or some other rigid object; don’t touch them with bare fingers, and don’t rub or scrape them off.

Rinse Sting with Vinegar

As soon as you can, pour household vinegar over the sting site for 30 seconds or more. This solution, which the U.S. National Library of Medicine notes is appropriate for reactions from any kind of jellyfish, neutralizes the stinging cells left behind on the person’s skin.

In the absence of vinegar, seawater can be used in a pinch. Don’t use fresh water to wash the sting site, though, as this can actually stimulate the stinging cells further.

Soak in Hot Water

Keep the sting site secured and as motionless as possible. When you’re able, soak the spot in hot water (about 107 degrees Fahrenheit) for a half-hour to an hour or so.

Apply Pain Cream

Afterward, use hydrocortisone cream or a lidocaine spray or ointment on the sting to treat lingering pain. Often, discomfort and redness from a sting fade quickly, but sometimes a painful rash may persist for weeks, in which case those balms may need to be reapplied for a while.

Top 5 Jellyfish Myths:

Here are some of the most common misconceptions out there about sea jellies!

- Jellyfish are out to sting you. ( Definitely not true—jellyfish aren’t inherently “mean,” and if they had their way, they would probably like nothing to do with you. The problem is (as we’ve covered), they can be tough to see underwater and aren’t strong swimmers, so it’s not all that hard to brush against their tentacles if you’re letting down your guard.

- Dead jellyfish are harmless. Again, we’ve already noted that you shouldn’t poke or pick up beached jellyfish with your bare hands: Those stinging cells can remain active for a long time after the creature dies.

- You should apply urine to a jellyfish sting. This is a widespread notion that, among other places, got some big-time airplay in an episode of Friends. But research indicates there’s no real evidence that pee stops the pain of a sting—and, in fact, some authorities suggest it could heighten the reaction.

- The Portuguese man-o’-war is the most dangerous jellyfish. First, we’ve established that the Portuguese man-o’-war is not a true jellyfish. Second, although the man-o’-war packs a serious ouch factor, it’s not as deadly as box jellyfish.

- All jellyfish deliver painful stings. While all true jellyfish can sting, the stings of many are imperceptible to people, and most of the rest are on the very mild side.

Top 10 FAQ about Jellyfish:

- How long do jellyfish live for? Can they die?

Typically, jellyfish do not tend to live for very long. Some smaller ones can last for as long as only a few days! In general, for around a year to a few years. Scientists have, however, discovered an “immortal” type of jellyfish called Turriopsis Dohrnii. Typically, jellyfish die from either being consumed by creatures within the sea or disease.

- Are jellyfish considered a fish?

Jellyfish are NOT classified as fish! They are invertebrates–animals without a backbone. The huge difference between a jellyfish and a fish is that fishes’ anatomy are centered around a backbone while jellyfish have no bone. That, and, the fact that jellyfish reproduce asexually and sexually throughout their lifetime, and fish reproduce sexually (and it is rare for a fish to reproduce asexually).

- Do jellyfish glow in the dark?

Yes, some jellyfish can glow in the dark. This does not mean, however, that every jellyfish glows in the dark. The glow in the dark effect is called bioluminescence: which is a light produced by chemical reactions happening within the bodies of the jellyfish. SO, why do they glow in the dark? Easy enough, self-defense is one of the reasons why. This light can help them camouflage within the sea floors, confusing predators that come their way. This light also helps attract larger predators as well, in hopes that they will prey on the more vulnerable predator coming for the jellyfish. Another reason why jellyfish use this light is to attract their own prey.

- Can a jellyfish sting you?

Yes, jellyfish can sting. Usually, when the tentacles brush up against a predator (or a human), it triggers the venom to be released and that is how the sting occurs. Stings vary in intensity: while some dial down after a few hours, others are more severe and can end in hospital visits, or even cardiac arrest (in worst cases.) Raised marks often take place of where the sting happened–which can last for days to weeks as well.

- What is the purpose of a jellyfish?

Jellyfish are more beneficial to the ocean than people realize. Some fish actually rely on the jellyfish as shelter! They use the jellyfish as a way to hide and protect themselves from predators. The environmental factor is hard to go unnoticed as well. The food chain within the ocean is another benefit that jellyfish lay within. Jellyfish eat on plankton, and some turtles and fish feed on jellyfish. It is the survival food chain of the waters.

- Do jellyfish have brains?

Jellyfish DO NOT have brains! Even though jellyfish don’t have brains, they DO have neurons that send signals all over their body. Known as the “nerve-net,” these nerves don’t need a brain to process thoughts.

- What is the deadliest type of jellyfish?

The Box Jellyfish contains some of the most venomous species of marine animals. These “sea wasps” contain tiny darts of poison all along their body. Getting stung by these can cause the most intense symptoms such as: cardiac arrest, paralysis, and even–death. The most severe species of the box jellyfish is the Australian box jellyfish.

- Why do they sting?

Jellyfish sting to capture and immobilize their prey. The venom acts as a defense mechanism when their tentacles brush up against something–or someone.

- What do they eat?

Jellyfish eat small plants (phytoplankton), zooplankton, fish eggs, small larvae, planktonic eggs, other jellyfish, shrimp, and crabs. Fun fact: turtles and ocean sunfish feed on jellyfish!

- How do you keep jellyfish away from you?

Use preventative measures! Wear protective clothing, stay out of the water, and put on a special lotion to protect your skin.

Looking for more Jellyfish FAQ? Check out “65 Questions Answered About Jellyfish”.

Other Things That Suck:

OK, maybe “suck” is too strong a word: Even the sea life that freaks us out has its ecological place, of course. (Well, except for those invasive lionfish…) But no question jellyfish aren’t the only creepy-crawly marine critters posing some measure of risk to us water-loving humans. Here are a few others, starting with that impressive sea-beastie we’ve been mentioning left and right throughout this article, the Portuguese man-o’-war!

Portuguese Man-o’-War: We mentioned that the Portuguese man-o’-war, which for all intents and purposes looks like a good-sized jellyfish, is actually a colony of tiny organisms living and working together. Those organisms are called zooids and have specialized functions to make the super-organism they compose work as a single unit.

The man-o’-war is named after the old-time warships it roughly resembles, thanks to the air-filled bladder or float that allows it to cruise along on the ocean surface. That vividly colored float, often blue or violet but sometimes pink, may extend six inches into the air. Below it straggles the man-o’-war’s great tentacles, which in exceptional cases may reach 100 feet long or more.

Armed with nematocysts like the tentacles of true sea jellies, those man-o’-war tentacles stun and kill small fish and other little prey.

The venom of the Portuguese man-o’-war causes a nasty sting in humans and leaves angry-looking, sometimes long-lasting welts. While mighty unpleasant, man-o’-war stings aren’t usually deadly. That said, a few fatalities have been reported, including in the American Southeast. Small children are most vulnerable.

Most common in tropical and subtropical waters, Portuguese man-o’-wars may drift long-distance on currents into more temperate zones. They often wash ashore, sometimes in large numbers. As with true jellies, avoid touching those washed-up man-o’-wars, as they can sting for weeks after beaching.

Potentially Dangerous Coastal/Reef Fish: Eels give some people the heebie-jeebies; others find them cool as heck, even beautiful. Either way, most eels are harmless to humans. Morays—several species of which inhabit Florida waters—have hefty jaws and a powerful bite. That said, they employ it only in defense, so the main issue is snorkelers and divers crowding or harassing the animals—or sticking their hands into reef holes, classic moray hideaways.

The spotted scorpionfish, another Sunshine State resident, sports highly venomous dorsal spines. Snorkelers and divers should practice caution exploring reefs—scorpionfish spines can penetrate wetsuits—and give these easily identifiable (but well-camouflaged) fish a wide berth.

The fancier-looking lionfish, not native to Florida but now established in many areas (and elsewhere along the U.S. East Coast), also have venomous spines that deliver painful, and occasionally very serious, stings. Two lionfish species are invasive exotics in American waters: the red lionfish and devil firefish.

The great barracuda is one of the most formidable predators of nearshore reefs and seagrass beds in Florida and elsewhere along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts of the U.S. Despite its big, fang-like teeth and impressive size—it may grow more than six feet long and weigh more than 100 pounds—the barracuda’s danger to humans is majorly overrated. That said, great

barracudas will shadow divers (mainly out of curiosity, it seems) and occasionally mistake a hand or foot for the small fish they prey on.

Sharks are also less dangerous than many people believe and are a big enough subject to warrant their own article. But we can’t NOT mention them, right?

Urchins: A variety of sea urchins—those rather beautiful spine-balls—inhabit Florida waters. A few species, among them the long-spined and black sea urchins, have venomous spines, and so are worth being extra careful around. The venom isn’t life-threatening but can make for a very painful wound, and a lodged spine—sometimes very tricky to remove—may cause infections.

Jellyfish Coloring Sheet

Jellyfish Videos

Jellyfish Sting Stories

Micke B.’s Story

I was on holiday in Australia in Busselton with my family, it was just a family outing for the day. There was a water park set up, like a lot of big floats where you can swim from one to the other and slide and jump off etc.

In the middle of the day, we noticed a lot of jellyfish floating around close to the surface of the water. They were small, almost see-through pinkish little jellyfish that seemed harmless. This time I was unlucky and there was one with tentacles and it wrapped around my arm.

In the water it felt like a slight sting and tingle, when I got out it was only burning a little and didn’t bother me, it started to get itchy but I never noticed anything or thought I was properly stung. Once we got in the car to go home I felt swollen bumps and took a picture as seen on my Instagram and then realized it looked like a jellyfish got to me and then it started to properly burn and sting. I couldn’t have my clothes touch or rub on it. I didn’t go to the hospital, I’m quite a tough cookie and just handled the pain until it went away. No major treatment, I just used a baby bum cream or thick cream for small burns to soothe the burning sensation. It healed fine, looked like small scabs, and then faded, no scaring or anything like that.

It definitely didn’t make me scared to go back into the water in the future, but I obviously had no desire to get back in on the same day. I was lucky that it was not traumatizing or a dangerous jellyfish 🙂

Ritnika N.’s Story

I am living in Goa, India-which is a beach town- and I have been here many years back and forth. On the day I got stung, I was just chilling with a couple of friends on the beach. People were joking that there was a big swarm of jellyfish, orange jellyfish with a long tail and I was like “yeah, I’m okay, it’s not gonna get us” and I had a couple of friends who were visiting and they were too scared to get into the water and I told them “Don’t worry! There’s not going to be any jellyfish, I have been swimming every day for a month and there’s no jellyfish–everything is going to be fine and if there’s going to be a jellyfish I am going to punch it for you!” Just joking around…so we all decided to go into the water, have a good time, and 20 minutes later; the couple I was with decided to stay in and I was like “Ok, I’m going to get out of the water”.

As I was walking out, basically when the wave kind of crashes, that’s when I felt something on my leg…and I looked down and saw something kind of orange…and because the wave was crashing, it got wrapped around my leg. I looked down and my instinct was to punch it because it was the only way to get it out because it got disoriented. And as soon as I got out I knew what had happened and I started screaming “I got stung by a jellyfish!”

I had actually been stung by a jellyfish before about 15 years ago in Goya. It was a different jellyfish… it was like a white, translucent jellyfish and that was bad, but this one was horrible. It was orange and long and because it had wrapped itself around my thighs, the area that it touched was such a large area…and my hand when I punched it also was burning. Luckily, the locals and I knew what to do. So the first step we used was hot water and vinegar, and that is it… except for one jellyfish in the world, there is no medication or cure. Don’t put regular water, don’t put saltwater, DO NOT PEE on the sting, haha. It does not help.

It literally took a month for all of the rash to go away and the burning to stop, etc.

I’m a water baby, I love the ocean. Am I scared to go back into the water? In general, no. But I am a little scared to go back to this certain body of water and this particular beach.

Rachel M.’s Story

In August of 2016, my family and I took a trip to Savannah, Georgia. One of our favorite things to do there is to take a drive out to Tybee Island to have a beach day and swim in the ocean. The weather was beautiful, but I did notice that the lifeguard station had a purple flag raised that day indicating wildlife present in the swimming area. This doesn’t always mean jellyfish will be present, but I knew that it was a possibility.

I was casually swimming later that day, being mindful of the fact that the water was quite cloudy and it was hard to see if there were any jellyfish in the water. I had been stung previously in this same area a couple of years before so I trod lightly and carefully until I swam out a little further until I was treading water. Then with one swift kick, I felt the very distinct electric, the burning-like sting of a jellyfish wrapped around my entire lower left leg. As I tried to free myself and swim away from its grasp, I kicked it with my right foot and eventually swam back to shore. The initial sting of a jellyfish does hurt, but dissipates quite quickly, leaving only some mild redness and a “raw” feeling on the area like when you touch a hot pan. I knew it was important to “deactivate” the stingers, so I headed over to the lifeguard station where they sprayed the area with a vinegar solution to treat them. Within about 10 minutes the pain was mostly gone and I continued on with my day even going back into the ocean a few more times.

Early that evening I noticed the sting on my leg had gotten progressively redder, but nothing of major concern. As I previously mentioned, I had been stung a couple of years before and I did end up having an allergic reaction that time (very red, hot, and itchy rash) about a week later, so I had thought that if I were to react like that again it wouldn’t be until we were home from our vacation. When I awoke the next morning, the entire area was very itchy and red and I noticed that little blisters had started forming on every part of my leg that the jellyfish had touched with a large blister developing on the back of my ankle. The area was also starting to swell and I had some pain in that leg while walking or standing. It progressed quickly from this point and later that afternoon we went to urgent care. The doctor had first started with a warm water soak on my foot/lower calf and used a tongue depressor to gently scrape the area to try and see if there were any barbs left to remove. I was then given an injectable antibiotic and anti-inflammatory along with two oral antibiotics and a corticosteroid to take for the next week. I recall both the doctor and nurse saying they had never seen someone react like that after a jellyfish sting!

The blister on the back of my ankle continued to grow until it was a good half-inch extending out from my ankle and soon my entire leg was covered in small blisters. But the worst part was the swelling. I had to sleep on my back with my leg elevated to both protect the giant blister and reduce the swelling in my leg. Every time I got up in the morning, I had to very slowly lower my leg otherwise the fluid would cause so much pressure too quickly and leave me in immense pain. At its worst point, you couldn’t even see my ankle since it was so swollen. The blister eventually broke and all I did was keep it covered and clean until it started to dry out.

The healing process was quite long. Eventually, all the blisters either popped or dried up, leaving me with skin peeling like a bad sunburn. I had some dark discoloration on the areas of the skin that were affected and lasted for at least a few months. I’m happy to say now that my leg and foot look completely normal and I can’t see any scarring from the sting whatsoever!

All in all, I’m still not afraid of the ocean, nor getting stung by a jellyfish, but I am much more mindful of the indicator flags at the beaches I visit so I can prevent it from happening altogether. While the sting was unpleasant, I absolutely did not let it ruin my trip in the slightest and I was able to enjoy the rest of my vacation with some minor adjustments!

Chrissy T.’s Story

Are You Ready For This Jelly?

I certainly was not! While happily riding the crashing ocean waves at Kure Beach, North Carolina, frolicking in about 4-4.5 feet of water, I pondered the possible location of the Great White shark that had recently been tracked off of the Outer Banks area. Straddling the boogie board resembling a plump seal ripe for a shark snack from below, I thought “Meh, too shallow for a shark that size.” I dove headfirst through the water’s crest, my endorphins pumping, not a care in the world, and then…..BAM! As the wave crashed over my body, I felt the punch of a heavyweight champion on the inside of my left arm near my elbow. My elbow suddenly felt a strange sensation somewhere between paralysis and burning. As my arm was still intact, I ruled out a shark bite and immediately knew who my perpetrator was. The initial sensation lasted a few minutes and remained centralized in my inner elbow area, but in the bright sunlight, it was hard to distinguish any redness on my skin. As the day continued, what looked like a 6-inch tattooed imprint of jellyfish tentacles formed around the inside of my elbow extending to my upper arm. I figured a little antihistamine would do the trick and by morning I’d be free of the wrath of the ancient ocean critter….or so I thought.

16 Hours After The Sting:

The next morning I awoke to prepare for a SCUBA dive 35 miles offshore. I took a quick look at my new jellyfish tattoo, and it now resembled what looked like a small surface scratch, maybe an inch long. “I guess I’ll have to get a real one” I chuckled. As fate would have it, the dive was canceled that morning due to gale force winds. I like to think that mother ocean was helping me out that day by preventing the dive because about an hour later, my arm erupted into a stinging, itchy, throbbing mass of welts. This seemed so bizarre as just a few hours ago it was nothing but a small scratch you might get from playing with a rambunctious kitten. Stubborn and determined to go diving at the end of the week, I soaked the area with apple cider vinegar and then smeared some topical cream on it throughout the day, trying to convince myself it would go away overnight.

65 Hours After The Sting:

The jellyfish tattoo had turned 3D, a cluster of blisters in the shape of two jellyfish tentacles surrounded by a bright red halo of inflammation that seemed to be spreading with each day, accompanied by an achy throbbing. Spoiler alert: the apple cider vinegar and topical cream were useless. I couldn’t ignore the worsening condition anymore, and the day that started with a drive to the dock for a fossil-hunting expedition, quickly turned into a trip to urgent care. The physician’s assistant that I met with was glad that I decided to get care, fearing that I was quickly on my way to a staphylococcal infection. He explained that although it’s rare, a jellyfish sting can lead to infection. The teeny, tiny harpoons on the jelly’s tentacles that pierce your skin to inject venom act as minuscule entry points for other bacteria to potentially enter your skin. I thought, “Wow! That would be super fascinating if this was a documentary and not my vacation”.

9 Days After The Sting:

While I was disappointed that instead of returning home with the teeth of the ancient Megalodon, I returned with a 10-day course of antibiotics, I felt somewhat intrigued that I had been branded by this unappreciated creature and needed to know more about it. I embarked on hours of jellyfish documentaries and research, and I suspect that the perpetrator was a type of box jellyfish, known to be increasing in population in that geographical area. And as I sit here writing this piece with 3 days left of antibiotics, I glance at the remnants of the sting, now flattened blisters and redness, just an annoyance at this point. I suspect to possibly have some scarring, my “jellyfish tattoo”, but at least I’ve gained some insight into what it takes to survive 600 million years.

Allison Fedor’s Story

It’s so funny to think back on this moment in time – the memory of it is so distant and far away now. But every time I look down at my chest, the reminder is there. A scar still so clear, with such a distinct shape, it can’t help but draw attention and eyes. It was the summer of 2013. I was 24 at the time, living in Spain, teaching English, and traveling every chance I could. My monthly stipend was more than enough to get by in Sevilla, but I moved back to Europe to travel! To explore! To adventure! To live life, and have endless experiences! So in order to make my wanderlust dreams come true all summer long, I decided I’d become an au pair! Au pairing was a great way to cut my expenses and go live somewhere new for the summer months. I started to look for families and landed with one in Palma de Mallorca, Spain. Mallorca? I think I’d heard of that! One quick online search and I knew: “I’m going to Mallorca!”

To live on a Spanish island during the summer is a highlight experience in life and one I’d encourage anyone who can to make it happen for themselves. You get to wear a sarong every day, and no one thinks twice! Because for all they know, you’re going to the beach, and most likely, you are! Living in a swimsuit, nice hot days, sunshine all the time, and lots and lots of adventures! I’d connected with a large group of expats on the island through my CouchSurfing community. We’d get together for someone’s birthday, all hike through the dense, intense wilderness for a couple of hours, then come out to find ourselves at a pristine Cala (cove). We would sleep on the beach, and wake up in a wonderland. It was incredible.

Often times we’d get ourselves to places only accessible by boat, and then hike back out before night fell again.

On this particular trip, I was with a small group. We went to a gorgeous little beach, plopped our stuff in the sand, and then stopped to admire the beauty of where we were. As I always have done when I’m around a body of water, I stripped down to my suit and waded my way in. The water was so pristine in these places, such a delicious feeling on the summer skin, and today I had my goggles, it was time to really swim!

I grew up in the water. To this day, my longest relationship is still swimming, and I haven’t swum competitively since 2009! I’m also a Pisces, so I feel right at home when I’m swirling around in the sea. I started to freestyle my way out, away from my friends old and new, away from the shore, away from the sand, out into bliss. Even though I had goggles on, my eyes were closed. Just to feel deeply into the experience, feel the water on every part of my skin, and release any tensions that might be held. It was a glorious moment, then suddenly, out of nowhere, like a thief in the night, I felt the most shocking pain!

It was electric! It was scorching, scalding, burning, intense, unknown, and completely took me by surprise! But before I could even fully process the pain I just felt, I felt it again, and again! I stopped moving, opened my eyes, and saw something that startled me to my core!

My eyes got HUGE, as I took in the sight around me: jellyfish, jellyfish, jellyfish EVERYWHERE! I was surrounded! I mean, in every direction I looked in, I saw them! I had unknowingly swum right into the middle of a swarm of jellyfish, and now I had to swim myself out, while my armpit and chest writhed in pain. Now, if you’ve never been stung by a jelly before, it’s very alarming! The burning sensation is phenomenal, and to receive back-to-back-to-back zings one after the other with zero processing time in between, left me in mild shock and fear. I quickly navigated myself back to the group, and in the most dramatic fashion, as I got close enough, I started to shout and yell in between my strokes, “NO! STOP! DON’T GET IN! JELLYFISH!!!!” It must have looked like something out of a movie, especially when I emerged.

I had that sting on my upper chest, another slight one across my bicep, and a couple of other smaller ones on the other arm. But I had no idea what to do! I’d heard you pee on it, so in what I felt was a completely normal fashion, I started asking everyone frantically, “Okay will you pee on me? Do you have to pee? Who is going to pee on me? Guys, I need someone to pee on me!” No one would do it. I couldn’t believe it! I’d just emerged from jelly-infested waters, covered in welts, and no one was willing to pee on me!

The real icing on the cake, came when one of the guys who was a band manager said, “You know, we do a lot of messed up stuff in the band, but I have never, NEVER, heard anyone ask anyone else to pee on them before!”

It became clear to me I’d have to be my own savior. So I grabbed someone’s water bottle, chugged it, then went behind a bush to pee into the bottle. Now, it’s not one of my proudest moments, but I had no choice… I poured the bottle of urine on myself like a shower, praying it would take the pain away.

It didn’t.

It did absolutely nothing. Nothing to ease the burning, nothing to take the pain away…not a thing at all. Again, I couldn’t believe it! The mark it left was remarkable as it scarred up, and it became even more impressive (as you can see in the photo). I became something like a living exhibit. I would go for dinner with the family I was with, and they would tell their friends who either worked or owned the place, “Look! But have you ever seen anything like this!?” One guy told me he’d lived there all his life, been a fisherman forever, and had never seen such a thing. The fact you could clearly see the entire body and tentacles was incredibly uncommon, and I wore it like a proud tattoo. I even decided I WANTED it to scar up, so I’d scratch at the scab to make sure it left a mark. And it has.

Eight years and ten days later, the mark is still here. I still see it when I look down, and other people often wonder how it happened. Every once in a while, someone will ask, and I get to retell them the hilarious and wild story, of My Little Squishy.

Natasha Tuck’s Story

In 2019 my fiance and I went on a summer vacation to Oahu, Hawaii. We had decided to rent a camper van and stay overnight parked at campsites while there. While staying at a campsite on the North Shore of the island we were warned about jellyfish and were instructed rather than swimming at the ocean beachfront area across from the campground to instead go down past a barrier where it was safe to swim. I love the water, I am often the first one in and the last one out. One evening while my fiance made dinner in the van I decided to take yet another dip. I was in the water for some time as the sun started to set around me. I knew dinner would be ready soon so I crept up to the shore, procrastinating actually getting out. Right along the shallow shore, I felt a sharp burn on my forearm. I stood up swiftly and held my arm for a moment. I had been stung before and knew this ache and burn. I had been stung again. I looked down and saw a minor red scratch, I held it knowing that wouldn’t help, gathered my items, and walked quickly back to camp. Calling to my fiance that I had been stung. He got a wet paper towel to put over it hoping to ease the burn. That’s when I got the first look at my arm. It was way worse than I had thought and what I was holding onto was an old scratch. I had 5 pale thick welts across my forearm, what appeared to be small bubbles like a burn and I watched as my arm got more and red around them.

The first time I was stung was on a beach in Jamaica a beach attendant told me NOT to pee on it and urged me to go back to the resort and get vinegar. So this time we did the same. We went to the front office which was closed. Luckily a kitchen dining hall area on the campsite had some workers inside. I told a gentleman in the kitchen area I had been stung and he poured some vinegar onto a paper towel and passed it to me. I showed him my arm asking if the reaction was normal and responded by handing me the whole jug of vinegar to take back to camp. It was the second-worst he had seen from the camp. To this day I wish I had looked down to see the little bugger that got me. I was told by the worker they were called the Portuguese Man O’ War and were not deadly or anything to be alarmed about. However, we did our own research for hours later on what was expected, switching damp vinegar paper towel arm wraps throughout the night. I still have light scars from the encounter but it did not stop me from going back into the water on that trip and the two stings I’ve had won’t stop me from swimming in the ocean again.

Hayatti Rahgeni’s Story

My husband and I were swimming in the ocean that day. We went swimming because I needed to practice my open water swim. I was preparing myself for a 1.5 km open water swim competition in Singapore. After we were done, I decided to stay in the shallow area. The water level was just below my knees. I played around in the water and I remember that I was standing there with my husband next to me. Suddenly I felt a sharp pain in my calf. I thought a fish poked me. I ignored it until I felt the sharp pain again on my other calf. This time it was extremely painful. It finally occurred to me that something was wrong and I decided to get out of the water fast. I told my husband that I felt pain in my calves and I quickly ran out of the water. I got to the shore and I was in pain. I sat down on the beach, inspected my calves, and saw a few swollen lines. I didn’t know what to make of them other than they were stinging. My husband approached me and asked me what was wrong. I showed him my calves and told him they were painful. It then occurred to my husband that I was stung by a jellyfish.

We didn’t have any vinegar with us. Instead, my husband suggested that I scoped and poured warm ocean water over my calves. That helped to soothe the pain however brief. I did it over and over until the pain subsided a little. It turned out that I wasn’t the only one that got stung that day. Sometime later an older gentleman came up to us and warned us about the jellyfish. My husband informed him that I got stung. The gentleman shared that he got stung too and showed us his thigh. He had a larger line across his thigh. We went home afterward and I let warm water run over my calves for some time. I didn’t use vinegar to treat my calves. The pain was on and off for about 24 hours. My calves were scarred the next day. I personally feel that I should have gone to the Emergency Room right away instead of trying to self-treat because one week later, the areas were infected and became extremely itchy. This happened while I wasn’t in my country and it bothered me throughout my trip.

Before that day, the thought of getting stung by jellyfish never crossed my mind because I had never experienced it. We had been swimming in the ocean a couple of times and I had never encountered jellyfish during our swim. I didn’t even think it was possible to get stung in the shallow area. I was wrong as I was standing in the shallow water when it happened to me. Getting stung by jellyfish that day did make me reluctant to go back into the water. However, at that time, I couldn’t afford to let my fear of getting stung stopped me from going into the ocean. I was very well aware that if I focused on the incident, then I wouldn’t want to get back into the ocean. Therefore I had to shift my focus. I focused on being able to finish my 1.5 km open water swim competition. Focusing on finishing my swims had enabled me to actively swim in the ocean for several years since then. To be honest, whenever I remember this incident and the pain that I had to endure, it makes me think twice about getting into the water.

Jo Crawford’s Story

My boyfriend & I were visiting San Pedro, Belize. There’s a restaurant called Palapas, & the restaurant is on stilts over the ocean water, so we were able to swim underneath the restaurant to get to the other side, instead of having to swim around it. So we swam underneath the restaurant & in the surrounding area. At one point while under the restaurant, the waves were hitting us & pushing us around, so at one point, I used my arms & legs to grab onto one of the restaurant’s stilts, which was covered in algae & such. Very soon after that, we got out of the water. As soon as I was exiting the water, I started feeling random spurts of stings on my inner thighs. They kept coming & going – noticeable & uncomfortable pain, but not horrible. I started noticing some redness on my inner thighs. It came on pretty fast. We walked to our hostel, the Sandbar, which is right in front of Palapas on the beach, & the tour guide who operates out of the hostel told me I had what the locals call “pica pica” which means “itchy itchy” in Spanish. He said it’s from jellyfish larvae. Every year, jellyfish release their larvae, which are microscopic, into the water, & when they come into contact with something, they release a toxin that stings. The locals who get in the ocean often come out with a case of pica pica just like I did. But he assured me that it was only a sting. It was not harmful, & I didn’t need to seek medical attention. The pica pica ended up being all over the inner part of my thighs & calves, which is where I was grasping onto the restaurant stilt. So I think when I grasped onto the stilt, that’s when I came into contact with the jellyfish larvae that may have been on the stilt. My boyfriend was in the water with me, but he didn’t get any pica pica, but he didn’t grasp onto the stilt-like I did, so that’s how I think I got it

Any time you get into the water, you always know there’s wildlife out there, especially in that area because there’s a large barrier reef nearby. So while I wasn’t aware of pica pica or ever thought about jellyfish larvae in my life, I knew there might be jellies out there. We had previously swum on a beach in Dangriga, Belize, & my boyfriend ended up with a tiny, transparent, squishy object attached to him. He said it hurt, & we had trouble pulling it off of him, but we got it off & got out of the water. It seemed like it might be a type of jelly, but we had never had an experience with that type before, so we aren’t sure what it was. Anyway, my point is, when we got in the water in San Pedro, we knew there might be jellies out there, but we weren’t too worried about it.

It stung sporadically, & then it would be calm & I didn’t feel anything. Then it would sting again. It wasn’t horrible, but it wasn’t fun either. As soon as the tour guide at our hostel told us what it was, he got some white vinegar from the kitchen & put it all over my legs. That made the stinging stop for the most part. Once it dried, I put some Benadryl cream on it. For the next few days, I put Benadryl cream on the pica pica as needed, so once or twice a day. It only lasted a few days, & then it was gone

I’m not afraid to go back into the water, haha. I’ve been in the water a lot worse. I swam with sharks & stingrays on that same trip, & I’ve been stung by other types of jellyfish in the past. It’s all a part of the ocean experience haha!

Maria S.’s Story

We went to Terrapin Nature Park in Stevensville Maryland for a picnic. After the picnic, we walked to the water on the Chesapeake Bay. I was with my husband and his mother. We were playing frisbee in the water and someone said they saw a jellyfish and then 30 seconds later one was wrapped around my leg so bad I had to push it off. I didn’t put anything on it and it stung for a day. The pain was pulsing off and on. It hurt really bad!

A couple of people on the trail that were leaving said they had gotten stung by jellyfish, but I didn’t think it would happen to me. When it happened, I yelled, “I got stung!” And it felt like it was stuck on my leg so I used my hands to brush my leg. My husband didn’t believe me when I went back to shore. He said, “are you sure you’re not imagining it?” I was so upset with him because it hurt so bad. To this day that is still a joke that I imagined. The red mark didn’t show up till later that night. The stinging was super intense and painful.

To this day, I am afraid to swim in the Chesapeake bay and I don’t think I’ll ever feel comfortable there. I didn’t do anything for aftercare, which I should have because it hurt for at least 24 hours. Throbbing and stinging pain that came and went.