Since the Chinese government first determined that the December outbreak of a mysteriously resilient pneumonia was a new affliction caused by the novel coronavirus, now called COVID-19, the global economy has reacted in increasingly drastic ways.

As the virus has spread, infecting hundreds of thousands in at least 147 countries, the travel industry has seen some of the most extreme economic impacts. A report by Tourism Economics estimates the travel and tourism industry could lose over $24 billion in foreign spending over the course of 2020.

To learn more about how the travel industry is faring in the wake of COVID-19, we compared tourism data from four travel destinations in the United States: Hawaii, Myrtle Beach, the Florida-Alabama Panhandle, and the Smoky Mountains.

Here are some of the most interesting patterns we found:

Short-Term Bookings Will Make or Break Summer Tourism Trends

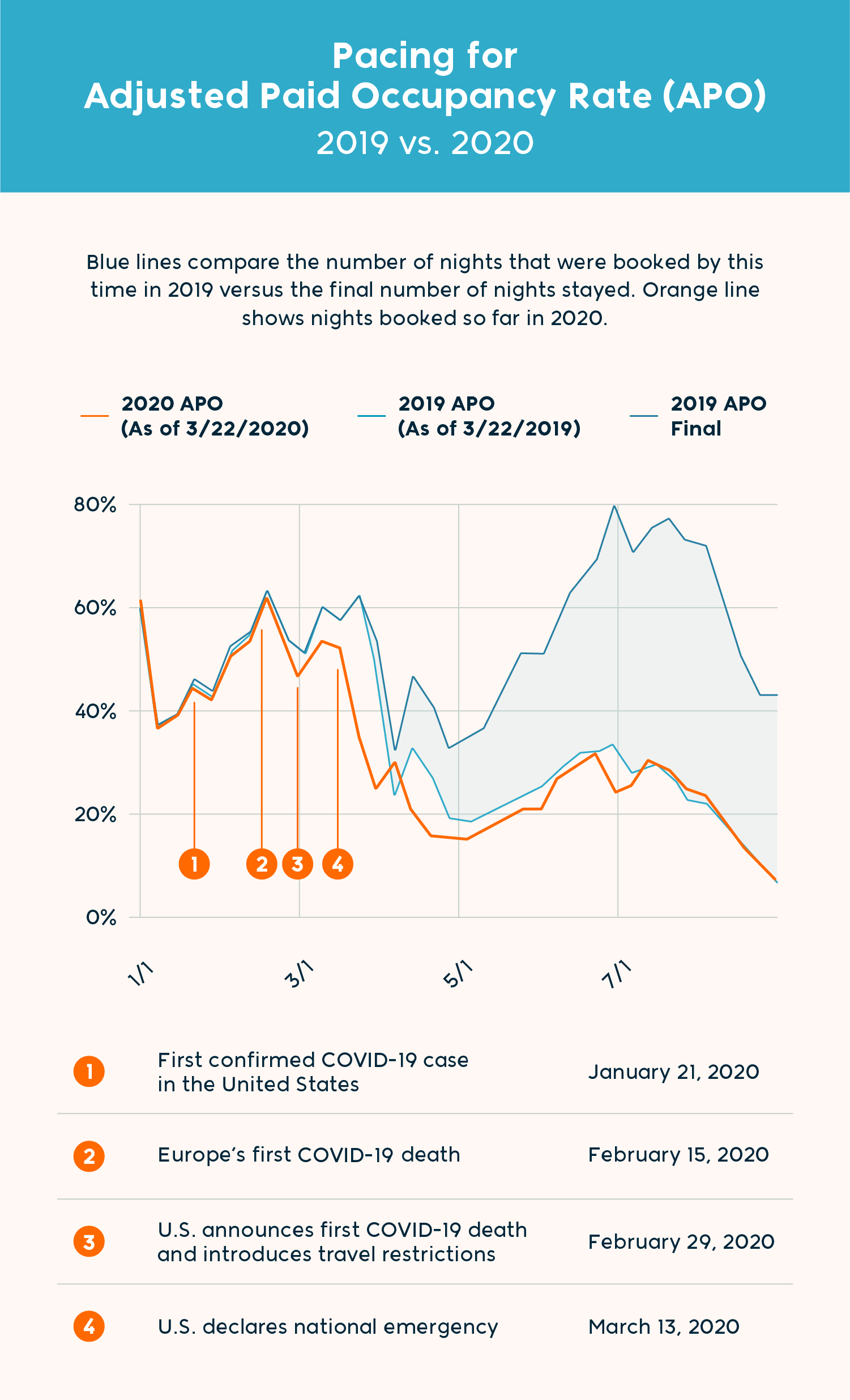

Though this year’s bookings for March through May have taken a dip following the coronavirus outbreak, bookings for May onward are on pace with what they were this time last year. This indicates that the lion’s share of 2019’s summer occupancy was made up of short-term bookings.

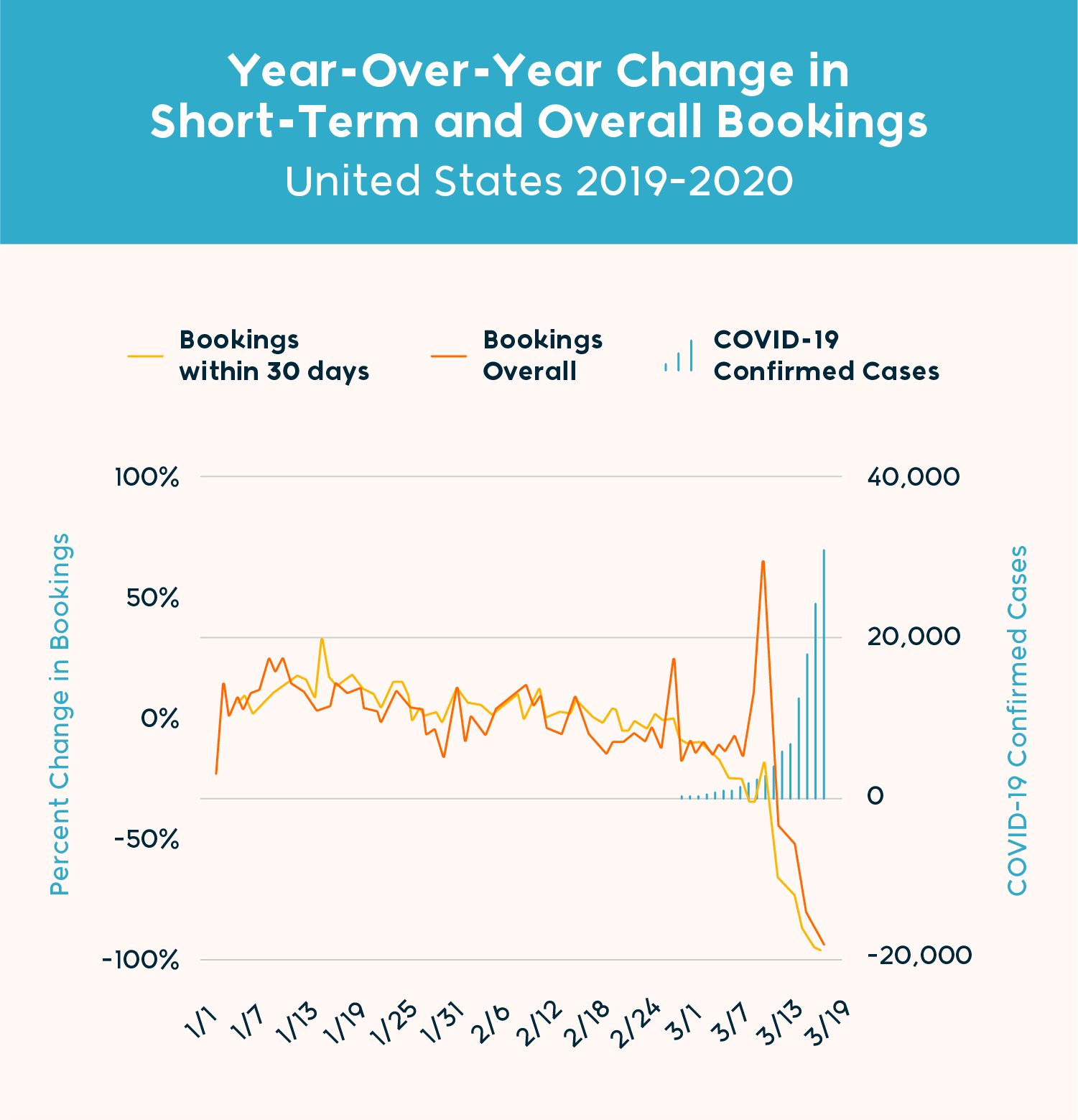

Unfortunately, short-term bookings nationwide are down by over 50 percent of what they were this time last year, while long-term bookings are down by nearly 75 percent.

Bookings for the peak summer season (the weeks surrounding the Fourth of July) are currently at 26 percent, which is fairly normal given that bookings for that same period were at just over 27 percent at this time in 2019. However, that means that well over half of last year’s Fourth of July bookings were made in the months leading up to the holiday—a pattern that is unlikely to repeat itself this year with coronavirus cases continuing to rise.

Plans Change Quickly as COVID-19 News Develops

One pattern that may offer encouragement to those hoping to salvage the summer tourism season is the tendency of bookings to react quickly to updated coronavirus news. We can see as we track nationwide data that patterns in travel bookings reflect different major points in the development of the coronavirus spread.

Most noticeably, short-term bookings skyrocket on March 12th as multiple states announce that schools closed due to coronavirus will not reopen before the summer. It’s likely that parents, looking to make the best of the situation, quickly started arranging last-minute vacation plans before the government declared a national emergency on March 13th, at which point bookings plummeted once again.

Spring Break Hot Spots Are a Departure from the Norm

Though short-term bookings for all four regions are now down by over half, not all have taken the same path to get there.

The timeline of national data shows clear downturns after several major events: overall bookings fall into the negatives after the first U.S. case is confirmed January 21st, and its downtrend deepens after the first U.S. death is announced along with travel restrictions on February 29th.

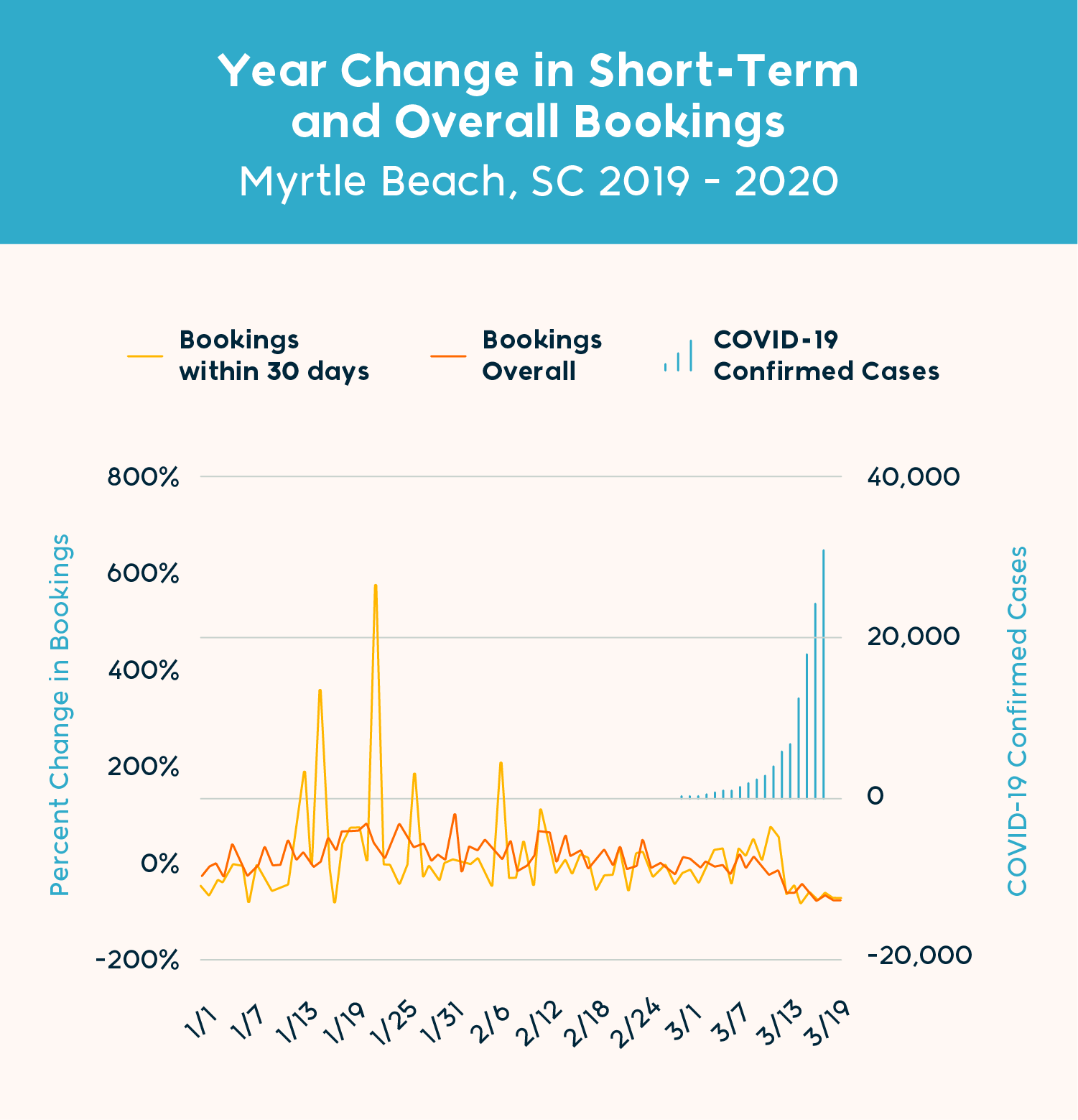

In one destination, however, the data shows patterns that are nearly the polar opposite.

In Myrtle Beach, a South Carolina beach town widely known for its popularity as a spring break destination, short-term bookings actually jumped after the January 21st domestic case is announced:

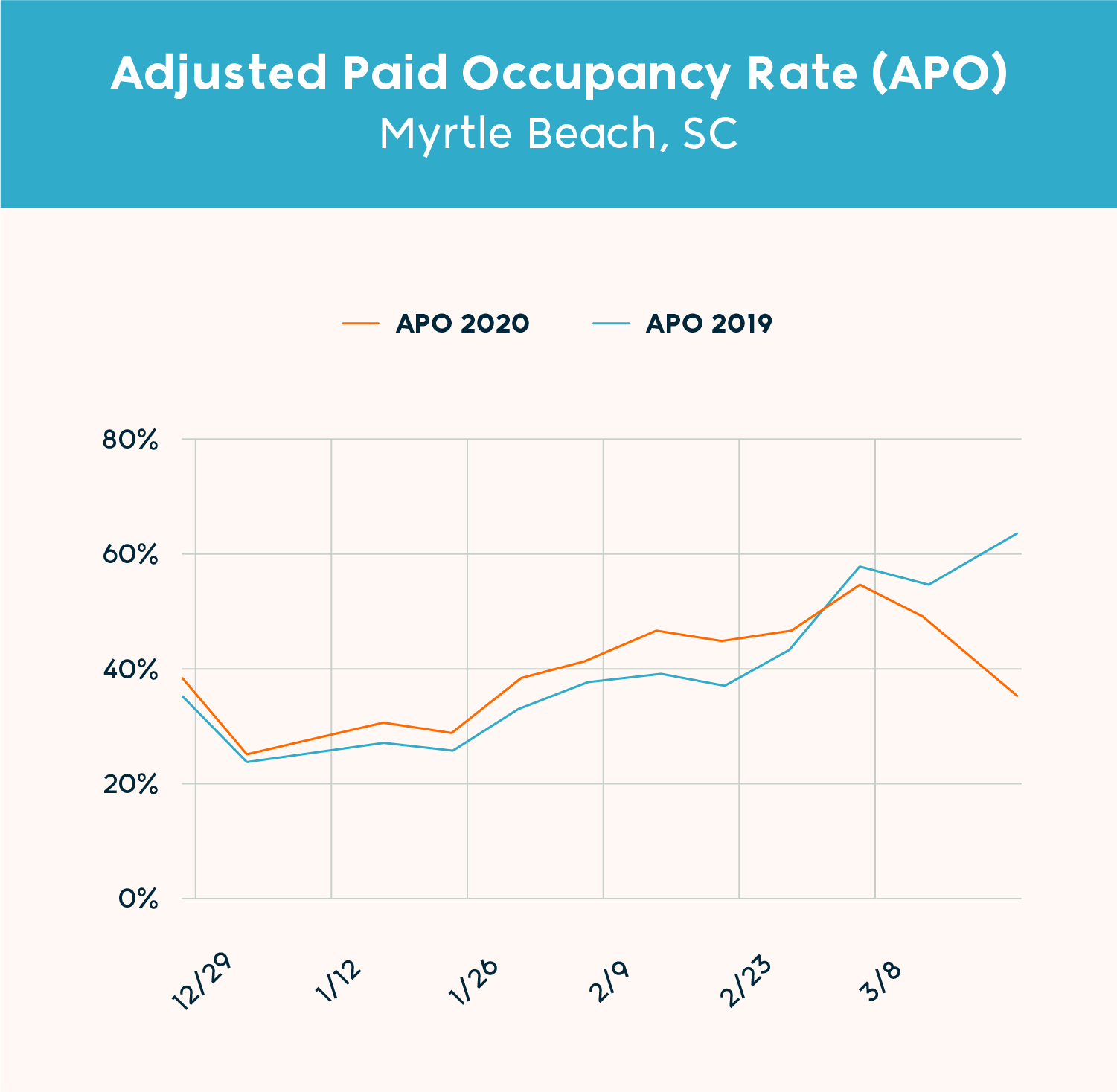

On January 23, Myrtle Beach short-term bookings climbed to nearly seven and a half times the rate of short-term bookings for the same date in 2019. Occupancy rates remained higher than last year’s numbers throughout the entirety of February, and have dropped a mere handful of percentage points in the first half of March.

As other states and cities shut down restaurants, close theaters, and implement curfews to curb community spread of the virus, many coastal towns have continued to see spring breakers celebrating in droves. With classes cancelled, college students have been free to gather on beaches and in bars, in Myrtle Beach and elsewhere, in defiance of the CDC’s recommendation to practice social distancing.

This trend is likely to drop off, however, as more and more local governments shut down beaches, bars, and restaurants and some states issuing full lockdowns preventing all non-essential travel outside the home. Thankfully, spikes in bookings to many other spring break locations dropped off again just as quickly.

Travel Sectors Bracing for Full Economic Impact

As individual shops, restaurants, and hotels shutter to ride out the pandemic, the travel industry is already seeing steep economic impacts that are likely to endure.

Globally, airlines have cancelled flights en masse, with flight capacity for March 16 down as much as 74 percent in countries with high infection rates, like Italy. In the United States, flight capacity is down just .5 percent, but the patterns set by countries ahead in the infection cycle offer a likely indication of what’s to come.

Many airlines continue flying their routes as scheduled, despite doing so with almost or completely empty planes, in order to retain ownership of the most valuable flight paths and time slots. Doing so comes at an astronomical cost — on United Airlines, for instance, flights must be at least 76 percent full just to break even with the cost of operating the plane. An empty plane can cost nearly $30 thousand dollars.

The next few weeks will be pivotal for the country’s health—both medically and economically. Countries like Hong Kong, which have locked down early and made COVID-19 tests widely available, have successfully managed to flatten the curve of the pandemic while others have suffered far greater losses. Politicians, medical professionals, and everyday citizens alike have issued statements pleading for others to stay isolated to help contain the spread of the virus. Outcomes for the travel industry, the global economy, and the wellbeing of the country will depend heavily on how well Americans listen. Pandemic holiday travel for Americans also relies heavily on the country’s response to the virus as well as Americans’ overall travel preferences during COVID-19.

Booking data via Key Data, used with permission.

COVID-19 outbreak data via the Johns Hopkins University of Medicine Coronavirus Resource Center.